Book Reviews

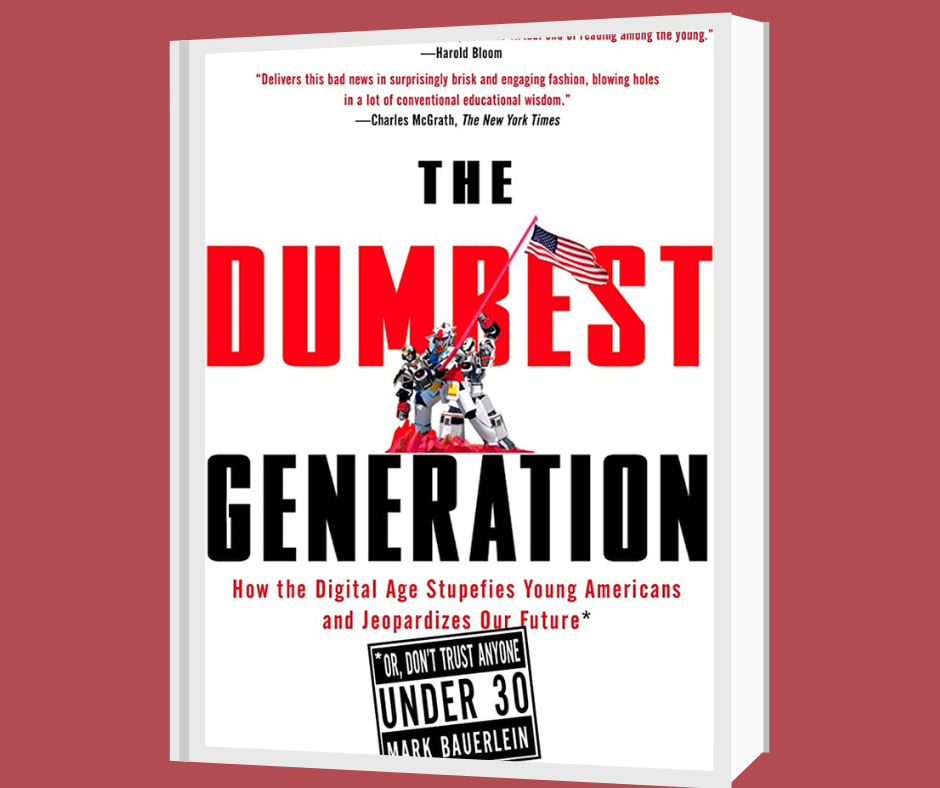

The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future *, by Mark Bauerlin | Review by Rosa Byler

(*Or, Don’t Trust Anyone Under Thirty)

Human beings seem to receive any new invention with a mixture of delight and apprehension. The automobile, the telegraph, and the printing press have all raised their share of early panic as well as praise for the progress they evince. Further complicating the picture is the tendency of the old to resist change and the young to embrace it, calling into question the traditional “wisdom of the elders” accepted by healthy societies throughout history.

Digital technology is no exception. From the first lumbering computers denounced as the mark of the beast to handheld gadgets considered indispensable, the “information superhighway” has provoked mixed reactions. Skeptical opponents are labeled stuffy, traditionalist, and impeders of progress, while those who joyfully hail (and purchase) each new improvement are considered innovative, astute, and avant-garde.

Now that the dust of the technological revolution has settled somewhat and digital media are an everyday part of our lives, what are some of the results? As definite patterns emerge, an increasing number of writers are beginning to address them. Various Christian critics have examined technology’s influence on the heart. Mark Bauerlin, a professor of English at Emory University, focuses primarily on its effects upon the “intellectual development” of young people, not their “behaviors and values…faith…or moral codes (7).” And he is disturbed, as the lengthy and insulting title of his book implies.

Bauerlin begins by citing statistics from “a variety of completed and ongoing research projects, public and private organizations, and university professors and media centers” representing “different cultural values and varying attitudes toward youth” which, remarkably, appear to be reaching the same conclusions (7). He documents these well. Impressive comparison charts, dating back to the 1950s and extending to include data from other countries, are interspersed with real-life examples of young people who are clueless and uncaring about core knowledge facts and principles that undergird democracy. (One of Bauerlin’s main concerns is the effect that these apathetic and culturally ignorant people will have on democracy in America.)

Bauerlin’s thesis is that children and young people, instead of being influenced by the knowledge and literature of history and the wisdom of their elders, are developing a peer-centered frame of reference. Their never-ending connectedness has produced a “vibrant online ecosystem” (135) that reinforces natural juvenile tendencies toward a “self-negating and self-aggrandizing” perspective (132). Lacking frequent and regular input from adults (and books), they remain perpetual adolescents. This topic resurfaces throughout chapters on knowledge deficits, “bibliophobes,” screen time, and the myth of online learning.

The author laments that the “custodians of culture” and “stewards of civilization” (161) who set learning standards should be standing up against this but are not: one chapter is entitled “The Betrayal of the Mentors.” (Two examples from the many cited: an article entitled “Who Cares if Johnny Can’t Read?” in Slate magazine and an editorial in the Los Angeles Times touting the educational value of video games [59, 60].) He concludes gloomily that unless something happens to reverse the trend, “the ramifications for the United States are grave (234).”

Who needs to read this book? Obviously, everyone under thirty should at least attempt it. Parents, teachers, and anyone who is in any way involved in education cannot afford to miss it. Be advised, though, that Bauerlin somewhat belabors his subject. He goes on and on. (As a self-acknowledged stuffy traditionalist and impeder of digital progress, I read the first chapters of the book rapidly and with increasing alarm. Bauerlin’s statistics made me want to effect instant and comprehensive media restrictions in our household and intensify our children’s reading program. However, the last half of the book was tedious going, making me wonder at first whether I shared more of the unlearned demographic’s traits than I realized.) After the unpopular subject matter, the book’s sheer wordiness is probably the main reason it has not been at the top of the best-seller charts. This is one book for which “grazing” is suggested. And it is worth noting that while the author references other works written from a secular perspective, he does not touch what Christians would consider the heart of the matter.