Book Reviews

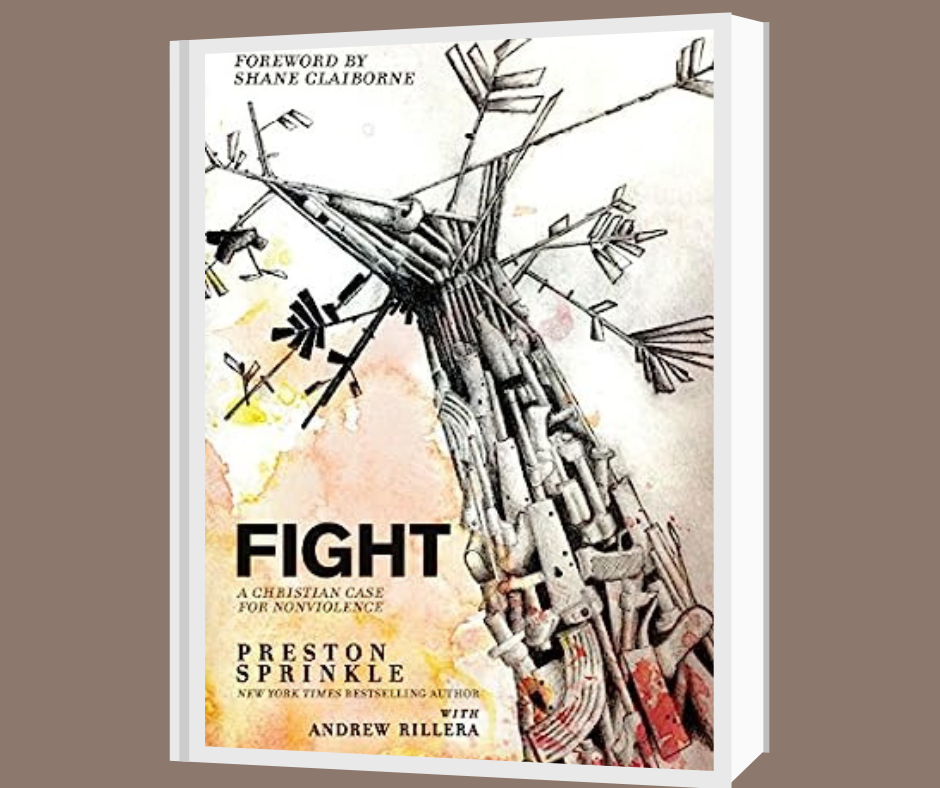

Fight: A Christian Case for Nonviolence, by Preston Sprinkle | Review by Rosa Byler

“Nonresistance” was one of two long and important-sounding “non-” words heard regularly across the pulpit in my childhood. With World War II fewer than thirty years behind us and military service still a requirement, Anabaptist churches were quite intentional about rehearsing Jesus’ teachings on violence. The ending of the draft in 1973 appeared to diminish much of this urgency, relegating the discussion mostly to gatherings of enthusiasts or weekend church conferences. Given the current level of evangelical support for militarism, now would be a good time to take a fresh look at what the Bible teaches about resisting evil. Fight: A Christian Case for Nonviolence provides just that.

Preston Sprinkle acknowledges that he is an unlikely candidate to do a whole-Bible study on nonviolence. He enjoys “sports…red meat…and watching violent movies”; and until he began teaching an ethics class at a Christian university in 2008, Sprinkle shared the view of many American evangelicals that “war and military might were the best way to fight evil (24).” Yet within a year’s time, an initially reluctant but honest investigation of the Bible’s teaching on violence brought him to his current position.

Since pacifism is easily misunderstood and is not uniquely Christian, Sprinkle uses the term nonviolence instead to express Jesus’ teaching on responding to evil (30). (Nonviolence and nonresistance appear to be slightly different concepts: Sprinkle’s unfolding description of nonviolence fulfills scriptural requirements, yet he does not make the same “nonresistance” applications that Anabaptists do. From the nonviolent perspective, for example, a Christian could be in the military or on the police force as long as he refrained from using violence [248].)

Sprinkle reviews relevant texts from Genesis to Revelation to demonstrate that shalom (peace, wholeness, harmony, joy) has always been God’s goal for His creation. Many Christians simply avoid Old Testament portions that seem to sanction violence; closer examination of such stories in their historical context reveals details that uphold the consistency of Scripture. As Israel’s King, God protected them; and although He allowed them to have kings, the restrictions placed upon these men were designed to keep Israel from militarism. Sprinkle points out similar explanations for the book of Revelation, full of martial language and imagery and considered by some “an embarrassment to Christianity (173).”

The period of four hundred turbulent years before Christ’s coming helps to explain why Jesus was not the sort of Messiah the Jews expected. Early church writings, however, show “widespread and diverse agreement” that Christians should never use violence and certainly should not kill (198). Whether Christians should be in the military was a much-debated issue of the time.

Scripture and early church writings notwithstanding, throughout church history some Christians have viewed nonviolence as an unrealistic position. Referencing well-known leaders from Augustine through Martin Luther on up to John Howard Yoder and the widely-read theologian Wayne Grudem, Sprinkle gives scriptural reasons for “respectfully disagreeing” with them. He also addresses several of the most common objections to nonviolence. What if someone were to attack your family? What about the “just war” theory? Killing another person is wrong, but what if it were “the lesser of two evils”? After telling a few stories of nonviolent responses that produced seemingly impossible results, Sprinkle concludes by reminding us that “[Christ] first served and suffered, and He invites us to journey with Him (256).”

Whatever the reader’s level of acquaintance with nonresistance/nonviolence, Fight will significantly deepen his understanding. (Even though my father was a nonresistance enthusiast, the Old Testament clarifications were new to me.) Scholars covering this extensive a scope of Scripture, theology, and history tend to produce works inaccessible to all but their intellectual peers. Sprinkle has obviously done his research well and documents sources thoroughly, yet he manages to keep the book simple and readable. Highly recommended!