Book Reviews

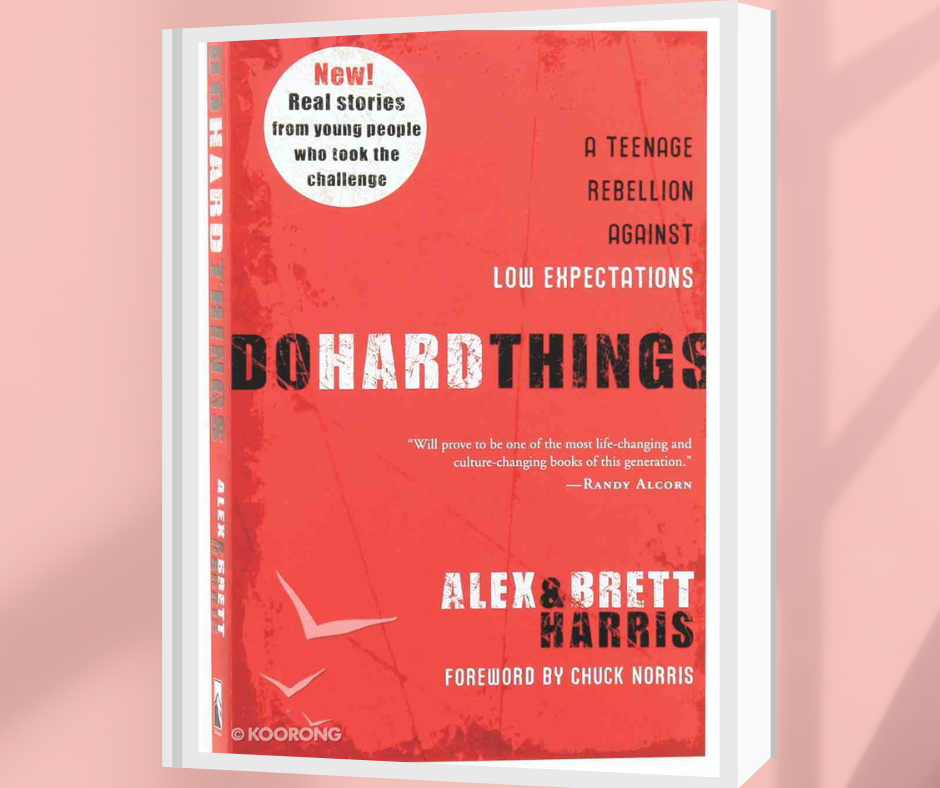

Do Hard Things by Alex and Brett Harris | Review by Rosa Byler

Do Hard Things: A Teenage Rebellion Against Low Expectations is a book written by and for teenagers. The aim of the authors, twin brothers Alex and Brett Harris, is to encourage young people to view their adolescent years as the “launching pad of life” instead of a time for having fun and accomplishing nothing.

Having left that stage of life with its opportunities and pitfalls more than thirty years ago, I approached the book with something less than enthusiasm. Its third-person-plural perspective, which made for a somewhat awkward writing style at times, added nothing to its appeal. However, I finished the book convinced that it should be read by more than just the target audience! While it is certainly good for adolescents themselves to set high goals and attempt to reach them, aren’t there others of us who should actively militate against a culture and a mindset that expects little from its young people? Why are expectations for the teen years so low? Whether you are a parent of young children or teenagers, a youth group leader, a pastor, or a teenager, you will benefit from reading this book.

The Harrises set the stage for the discussion by examining how our culture has arrived at its view of adolescence. The Bible does not speak of teenagers; the apostle Paul, for example, seems to have moved directly from childhood to manhood without an in-between period of looking like a man while acting like a child. The authors give examples of young people of the 1700s and 1800s who did hard things, apparently without a second thought; it was expected of them. Until about a hundred years ago, children were an important factor in family economics and contributed their share as a matter of necessity and normality. How and when did the “myth of adolescence” originate? (The word teenager first appeared in a Reader’s Digest article of the early 1940s.)

The child-labor and school-reform laws of the early 1900’s were intended to protect children from workplace abuse and provide for their education. However, as children began to move into young adulthood without taking on the role of producer and contributor, they remained consumers for a much longer period of time. And as society ceased to expect “competence, maturity and productivity” from its teenagers, young people measured up (or down) to exactly what was expected of them—resulting in a new social stratum that enjoyed nearly adult freedom while taking on few adult responsibilities.

After an interesting illustration of how expectations can shackle performance, the Harrises present what they call “five kinds of hard”: things which are outside the comfort zone; things that go beyond what is expected or required; projects that are too big to accomplish alone; tasks that don’t earn immediate payoff; and choices that challenge the cultural norm. Over the next chapters, these categories are illustrated by examples of contemporary adolescents who started practicing them in spite of physical challenges, personal fears, and scorn from bystanders. There is also a chapter on small hard things: tedious, repetitive tasks that don’t seem very productive or glamorous but that constitute the fabric of daily living and help to develop character for the big tasks of the future.

Do Hard Things is easy to read, yet thought-provoking. While it lacks the depth of insight older writers might contribute, it is written from a Christian perspective and has much to offer adolescents (and their parents and leaders) who have simply accepted our culture’s expectations without much thought. It is a good starting place for anyone who needs inspiration and a “push” to move beyond the customary and the acceptable to the good and the better!